The concept of "herd immunity" has been controversial since the beginning of the epidemic.

Two recent papers in The Lancet and Science have brought herd immunity back into The picture: a Brazilian city that was once thought to be herd immunity is once again experiencing a peak.

76% infection rate, herd immunity formation

Manaus, Brazil's eighth largest city, is located in the Amazon rainforest and has a history of more than 500 years.

But Manaus's fragile health system collapsed once in a few months, thanks to the heat and poor resistance to the disease.

But after the initial peak of the epidemic, the rate of infection in Manaus unexpectedly declined. Starting in May, the rising number of confirmed cases in Manaus began to decline, and by August the rising number of deaths was close to zero.

On Jan. 15, Science published a paper on the Manaus epidemic.

Screenshot of Science Paper

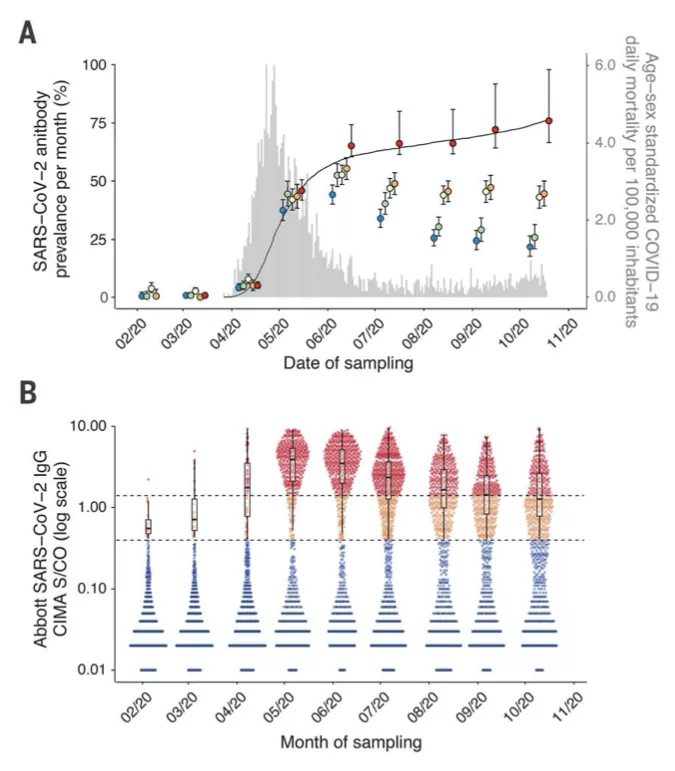

The researchers took blood samples from Manaus in different months and tested them for the COVID-19 antibody IgG.

After infection with COVID-19 antibody IgG can be detected for a period of time after the patient recovers. Therefore, the IgG-positive rate in the general population can be approximately equal to the prevalence of COVID-19 in the population.

In April, prevalence in Manaus, Brazil, was 4.8% (95% confidence interval 3.3 to 6.8%). By May, that number had grown to 44.5% (95% confidence interval 39.2 to 50.0%). In June, it peaked at 52.5% (95% confidence interval 47.6 to 57.5%).

However, entering 2021, the epidemic which had seemed to be calm, was revived.

In the first three weeks of January 2021 , there were 1,333 COVID-19 cases in Manaus. On January 14 and 15 , 29 patients in Manaus died of COVID-19 due to oxygen shortages, CNN reported.

January 11th. "This is something that no one expected," Brazilian Health Minister said on a trip to Manaus to monitor the outbreak. "It's moving so fast."

Why does "herd immunity" fail? A paper published in The Lancet on January 27th makes four points.

Screenshot from the Lancet paper

First, the 76% infection rate is, after all, a figure derived through modeling, correction, etc., and is subject to error. Before the peak of the new wave in December, Manaus may not have actually met the criteria for herd immunity.

Second, a British study suggests that serum antibody titers decrease over time after infection, which may also explain why secondary infections occur.

The majority of cases in Manaus were infected between March and May 2020, so serum concentrations of COVID-19 antibodies in recovering patients may not be sufficient to provide effective protection after 7 to 9 months.

Third, the new crown antibodies in the sera of previous infected people may not be able to fight the mutated strain.

The mutant strains currently circulating in Brazil include B.1.1.7 and P.1, of which the P.1 mutant was first detected in Manaus on 12 January. A preliminary study found that the P.1 mutant strain accounts for 42% of the current cases of COVID-19 infections in Manaus.

In addition, a new mutant has recently been detected in several regions of Brazil, including Manaus: P.2, a sublineage mutant of B.1.128, which, like P.1, has E484K mutation in the spike protein.

However, several previous in vitro experiments have shown that E484K mutation may cause immune escape of COVID-19, reducing the effect of neutralizing antibodies.

In other words, people who were previously infected with Manaus could still be reinfected with the new mutated virus.

Finally, if a highly transmissible mutant becomes an epidemic strain and R0 therefore rises, so does the percentage of the population needed to achieve total immunity, the established herd immunity may be broken again.

However, further studies are needed to prove whether the transmissibility of P.1 strain is improved.