Q: What did you do with the other embryos? Were they implanted?

A: There are seven couples but the clinical trial is on hold due to the current situation.

Q: What did you to get feedback on the clinical trial design? What was the scope of the team and where did you go to get approvals?

A: I first talked with a couple of scientists and a doctor to find out whether CCR5 was the one recommended. Once we had some data, I presented at Cold Spring Harbor in 2017 and also at the Berkeley genome editing conference. Some of the others in that conference too. I received positive feedback and also some criticism and also some constructive advice. I continued to talk with not just scientists but also the top ethicists in the United States such as at Stanford and Harvard. I also showed my data to visiting scientists. When I started a clinical trial for the informed consent, we.. as a reference.. and drafted a consent form. The letter was reviewed by a US professor. ... Subsequent... follow-on plan.

Q: How many people reviewed the informed consent and felt it was appropriate?

A: About four people. ...

Q: On the informed consent issue, was that an independent person talking to the patient, or was your team involved in that process directly?

A: ... team member went to talk to the volunteer first for 2 hours, and then after 1 month, the volunteers came to Shenzhen and I personally took them to another professor and gave them informed consent.

Q: So you were directly involved?

A: I was involved. Also, I brought them the information about off-targets and so on.

Q: How did you recruit these couples into your study? Was it done by personal connections? Did your institution put out a release? How was recruitment done of these particular couples?

A: It was by an HIV/AIDS volunteer group.

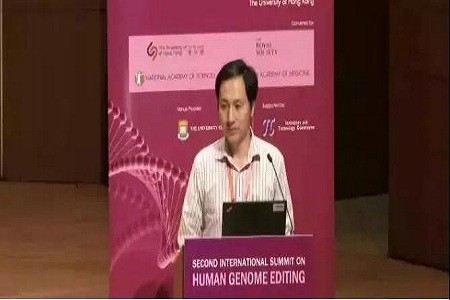

Q: I think what we should do now is... start answering questions from the floor. David Baltimore would like to say a quick word first, if possible.

When it comes to taking questions, I will take questions from the general participants who are lined up. I will also... I have questions from the media. I have a lot of questions. Many of them are the same. I'm not going to say who asked the questions, because they are the same questions. But quite a few of them have already been answered during Dr. He's talk. I will be quite selective. First, David.

David Baltimore

I want to thank Dr. He for coming and being responsive to the questions that have been asked. I still think that the statement that we made at the end of the last meeting, was that it would be irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of germline editing unless and until the safety issues have been dealt with and there is universal societal consensus, that this has not happened, and it would still be considered irresponsible. I don't think it has been a transparent process. We only found out about it after it happened, so we feel left out. After the children were even born. I personally don't think it was medically necessary. The choice of disease we heard discussion about earlier today are much more pressing than providing to one person some protection against HIV infection. I think there has been a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community because of the lack of transparency. I am speaking here entirely for myself. The committee that organized this meeting will be meeting and issuing a statement, but that will not be until tomorrow. Tomorrow? Tommorow. And why don't we continue?

Questions

...

Q: I'd like to echo David Baltimore's comments thanking you for coming here under some unusual circumstances. First, I don't see the unmet medical need for these girls. The father is HIV positive and the mother is HIV negative. You already did sperm washing, and thus you already could generate uninfected embryos that could give rise to uninfected babies. Could you describe what is the unmet medical need, not of HIV in general which I think we all appreciate, but what is the unmet medical need for these patients in particular? Second, you justified the critical decision of implanting these embryos to create a human pregnancy with the decisions made by the patients rather than made by the scientists, doctors and ethicists. Can you comment on what is our responsibility as scientists and doctors and independent communities to make that decision for the patients rather than allowing them to make that decision seemingly on their own? Thank you very much.

A: The first question was whether CCR5 is an unmet medical need. I actually believe that this is not just for this case, but for millions of children. They need this protection. HIV vaccine is not available. I personally experience with some people in AIDS where 30% of a village people are infected. They even have to give their children to relatives and uncles to raise just to prevent potential transmission. For this specific case, I feel proud. I feel proudest, because they had lost hope for life. But with this protection, he sent a message saying he will work hard, earn money, and take care of his two daughters and his wife for this life.

Q: Before we get to the second question, you said there has been no other implantations. Just to be clear, are there any other pregnancies with genome editing as part of your clinical trials?

A: There is another one, another potential pregnancy.

Q: You said early stage? So chemical pregnancy?

A: Yes.

Q: I have a two-part ethical question. Could you slow down a little bit and talk about the institutional ethics process that you said you went through. Looking to the past. The second part is looking to the future- how do you understand your responsibility to these children? Your last slide indicated that you would be doing follow-up treatment. What is your responsibility towards the future as well?

A: Do you see your friends, your relatives who may have-- a genetic disease-- the way I see it, those people need help. There are millions of families with inherited diseases or or exposure to infectious disease. If we have the technology and can make it available, then this will help people. When we talk about the future, first it's a transparent open and share what knowledge I accumulate to society and to the world. It is up to society to decide what to do next.

Q: What about the actual children? It was not an abstract question. Going forward with these born children, how do you understand your responsibility to them?

Q: It relates to questions from the media. Will you publish the identity of Lulu and Nana in the future? Will it effect things if the individuals remain secret? You really have to protect patient identity in this case. The world wants to know, they will want to know whether they are healthy, whether the method had any negative or positive consequences. How will you deal with this?

A: It is against Chinese law to disclose the identity of HIV positive people in public. Second, for this couple, it's under careful monitoring. I will propose that the data should be open and avaliable to experts.

Q: How did you convince the parents when you started this expeirment? Did you tell them about alternatives to avoid AIDS infection of their child? And how did you do the ethical review? How was the process? How many institutions?

A: So the first question regarding how we convinced the patient. These were volunteers. They all have good education background. They had a lot of information about HIV drugs and other approaches, and even some of the latest research articles published. They were usually in a social network together where the latest advancements in HIV treatment is available. The volunteers were given informed consent, and they already understood quite well about the gene editing technology and the potential effects and benefits. I think it's a mutual exchange of information.

Q: Back to transparency, would you be willing to post the informed consent and your manuscript in a public forum so it could be reviewed such as on biorxiv.org or a public website for informed consent so that the community can read in detail what you have done?

A: Yes, actually the informed consent is already on the website. Search my name and you will find it. Second, for the manuscript, when I drafted the manuscript there are already about 10 people-- a few in the US-- have been editing (reviewing?) my script-- I will send several to give comments. I might (not?) submit to biorxiv. It should go to peer review first before being posted to biorxiv.

Q: You took that advice, but would you change your mind now? The circumstances have changed, and there is big demand to know what you have done. That's not a question I suppose, but just something to think about.

Q: I am very interested in informed consent process. You said there's a consent form that you are happy to share, it was reviewed by four people, and a ten minute conversation that happened with the patients. In the UK, the average reading age of the general public is around age 10. The vast majority of the UK public doesn't understand the word genome. I'm quite interested what happened in that conversation. How did you explain the risks? What was the evidence that they understood?

A: I did not say 10 minutes. I said 1 hour and 10 minutes. It happened in a conference room where the couples met and two observers. Printed copies were given to the couple before informed consent.

Q: Could they read them and understand them?

A: Yes. They were very well educated.

Q: Okay.

A: Yes. I explained from page 1 to page 20, line by line, paragraph by paragraph. And they had the right to ask any question during this informed consent process. Once we went through the entire informed consent, at the end I gave them time to private discussion so that they had some time to discuss as a couple. They also had the choice to decide to take it home and decide later.

Q: Were any of the team members trained in taking consent? Was this the first time? Were they trained at doing this?

A: I had two rounds of informed consent. The first round was informal and a team member from my lab. Just two hours to talk with them. The second one was more formal, and with me. I read guidelines from the NIH on informed consent when we drafted the informed consent.

Q: Question from the media, could you please explain the source of the funding for this work?

A: When I started this, I was a professor at a university. Three years ago, I began this work. I began that when the university was paying my salary. Medical care and expense for the patients was paid by myself. Some of the sequencing costs was covered by startup funding in the university.

Q: So there was no funding from industry or a company? Just to make it clear, you have involvement in a company, but that was not involved in this project?

A: Neither my company was involved in this project, neither people space or equipment.

Q: Did the families pay anything or did they pay anything? Was there any exchange of money?

A: We explained in the informed consent that we paid all the medical expense and they would not receive money for this.

Q: Who should be responsible for these patients? How will medical care be provided? How will you evaluate their mental health due to strict supervision? What about vaccinations and neurodevelopmental outcomes?

A: .. informed consent provided information about regular blood tests and other medical procedures. It's all available in the informed consent document.

Q: Regarding off-target assessment. You mentioned you did single cell whole genome sequencing. As far as I know, there is no reliable or mature technology to conduct single cell whole genome sequencing. So how did you do this? There's also consensus to not allow ... to conduct genome editing on germlines. This is the consensus of the international community including the Chinese community. I assume you were aware this was a red line. Why have you chosen to cross this red line? Why did you perform these clinical trials in secret?

A: First, regarding off-target by sequencing. Before implantation, we can biopsy only 3 to 5 cells from the blastocyte. From that, we amplify for single cell. We were able to get maybe 95% genome coverage for single cell. Or 80-85% coverage, current state of the art. There might be off-target effects missing, but it's not just looking at this embryo, we had many of them, and by many of them together we can understand how much off-target happens.

Q: The second part of the question, was, why so much secrecy around this particularly when you know the general feeling among the scientists is that we shouldn't be doing this? Why so much secrecy from the Chinese authorities? You know the accusation now is that you have broken the law. If you had involved the Chinese authorities, they might have said you can't do it. That's how it seems, you went ahead anyway.

A: I have been engaged in the scientific community. I spoke at Cold Spring Harbor, Berkeley, and at an Asian conference. I consulted them for feedback. I moved on to clinical trials, and at that time I also consulted with experts in the United States about ethics.

Q: There were many scientific questions raised. But there's also a very personal dynamic for these two girls. If things had been thoroughly vetted, there might have been a proper discussion. So there are two sisters, and one is refractory to HIV infection and that was a desired outcome from the parents or at least the father you specifically highlighted. Within the family dynamic, are these daughters going to be treated differently? The othe rside of that is the one girl that is refractory to HIV infection- is she now going to be desirable for breeding? Will this change her whole dynamic in terms of marriage and children because a spouse might be particularly interested in getting this mutation within the family? Even this very simple thing, with these two girls being different and the family and now this being something of an enhancement preventative trait not just a disease correction but now something new that could be introduced in the population.

A: I have reflected deeply on this. This is why I published the five code value for gene editing. First is respect for children's autonomy. These tools should not be used to control their future or make expectations about their future choices. They should be given the freedom of choice. The second one is-- the children, encourage them to explore their full potential and the pursuit of their own life.

Q: For 18 years though, they are children and they do not have that autonomy. Their genotype might quite affect their upbringing. Will this effect their perception, or their parents?

Q: Their parents will know they were edited.

A: I don't know how to answer this question.

Q: I've been told we have to stop this session soon. I want to finish off with two questions from the media, some that have been repeated several times. Did you expect all this reaction? Even if you had managed to succeed in having the paper reviewed and published first, there would have been a lot of fuss at that time as well. Did you anticipate this?

A: It's because the news leaked out. My original thinking was based on the survey of the United States or the US or the British ethics statement or the Chinese study that gave us the signal that the majority of the public is supporting human genome editing for treatment including HIV prevention.

Q: The very final question is, if this was going to be your baby, would you have gone ahead with this?

A: That's a good question. If it was my baby, with the same situation, yes I would try first.

Q: I think we should thank Dr. He for appearing here.